Pushing Cases to Resolution

All too often in litigation, justice delayed is justice denied.

Former Georgia Court of Appeals Judge Dorothy Beasley could have been speaking about any one of countless cases pending in the courts of this state (or any state) when she remarked in the case of Ogletree v. Navistar Intern. Transp. Corp., 236 Ga.App. 89, 511 S.E.2d 204 (1999), quoting from Charles Dickens:

Now in its fifth appearance before this Court, this tortured and protracted litigation … conjures up images of the generations-long odyssey of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce of Bleak House fame: “And thus, through years and years, and lives and lives, everything goes on, constantly beginning over and over again, and nothing ever ends…” The law sometimes weaves its garment painstakingly slowly.

Although set against the backdrop of the mid-nineteenth century English legal system, Dickens’ Bleak House is in some ways disturbingly reminiscent of twenty-first century American litigation. All too often it seems as if “nothing ever ends.” Clients would be better served if our court system tolerated fewer delays, if litigants were more regularly sanctioned for turning the discovery process into the de facto battleground, and if more attorneys had the courage to push their cases to trial as quickly as practicable and try them to verdict.

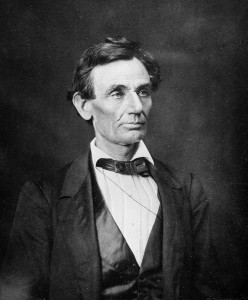

Ironically, that is exactly what lawyers practicing in a much more primitive American legal system used to be able to do over 150 years ago – at exactly the same period that Dickens referenced in his critique of the English legal system in Bleak House. Writing about Abraham Lincoln’s practice as a country lawyer prior to becoming President, biographer David H. Donald described Lincoln riding a judicial circuit in rural Illinois, traveling by horse along with a band of other local lawyers, as well as the local circuit judge who would hear the cases they tried in each of the counties comprising the circuit:

[T]he caravan moved on toward the next county seat. Arriving on a Saturday or a Sunday, the lawyers resorted to a favorite hotel or tavern near the courthouse, where they slept two or three to a bed.

The next morning the lawyers would be approached by litigants… Business had to be transacted speedily – declarations and traverses drafted, petitions written, lists of witnesses drawn up – so that the judge could hear cases on Monday afternoon.

David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (Simon & Schuster, 1995) p. 105-106.

The idea of being able to meet a new client in the morning and try his or her case to verdict the following afternoon is not an experience even roughly approximating anything that any modern American civil practice litigator has ever experienced. Although there are many reasons why modern litigation is much more complicated, expert-driven, and discovery-intensive than the cases that Lincoln tried on the circuit in the 1840’s, a large part of the habitual delay in the American legal system is avoidable – unnecessarily driven by the lawyers on both sides – and it should be resisted at all costs.

Much of this modern American problem is beyond the control of any individual lawyer. The progress of the law somehow seems intent on inventing an increasing number of obstacles – e.g. Daubert, Iqbal, etc. – that prevent us from simply trying our cases to impartial jurors and letting the chips fall where they may, as the Framers intended when they drafted the 7th Amendment to our Constitution. Our overburdened and underfunded court system also makes it simply impossible for all of our cases to reach the top of the trial calendar within a reasonable time. (We can be thankful that at least the Georgia appellate courts are bound by the “two term rule.”)

However, it is our obligation as trial lawyers, as effective advocates, and as guardians of our clients’ trust to be vigilant against this problem at every turn – and in every single case that we handle. Although most cases will settle, the best results are almost always obtained by those who are ready, willing, and able to try their cases to verdict. At the Smith Law Practice, our goal – and our promise to our clients – is to proceed from intake to “ready for trial” as quickly as possible.